“Iolani Palace” by Joel, used via CC 2.0

“Now we know”: Eight reasons why so many Kānaka Maoli oppose US federal recognition

“My grandmother knew and spoke to me about the events of 1893. She lived to be 100… fortunately, she lived often with us and so what I know is…my family said no to the Committee of Safety and to the provisional government…we said no in 1897 to annexation and signed the Hui Aloha ‘Āina petition here on Maui and in Honolulu…Years later I asked my mother, how did she vote in 1959 to the question about Hawaii becoming a state, and she said no. Now we know our history, we know what happened here in 1893, and we know that we are not an Indian tribe and not to be treated as such.”

(Waters Omar Fin, Jr., July 7, 2014 in Lahaina, Maui)

“Now we know that there was no treaty of annexation and we also know now that the joint resolution as an act of Congress has no power to acquire any island. An act of a legislature or an act of parliament has no power outside of its country to acquire dominion of another. If that were so, Hawaii could acquire the United States and probably should have…I want to say no, no, no, no to federal recognition, no to occupation, and no to the United States. Thank you.”

(Williamson Chang, June 23, 2014 in Honolulu, O‘ahu)

A few days ago, the US Department of Interior (DOI) released its final rule with regard to establishing a process to federally recognize a Native Hawaiian government, subject to the plenary power of the US Congress. What happens next will hopefully involve vigorous debate in the Hawaiian community over questions of government and of the relationship we believe Hawaiʻi should have to the US. Most importantly we should talk about how our collective next moves impact our lands.

As we prepare for and engage in those discussions, we should return to the outpouring of sentiments and analyses that came out during the 2014 public meetings held by the DOI in Hawaiʻi. These were the only face-to-face public hearings EVER to be held across the archipelago on the topic of US federal recognition.

E kuʻu mau hoa ʻŌiwi, no matter where you stand on the issue of federal recognition, please take the time to really listen to the voices that poured forth at these meetings. I have too often heard these testimonies dismissed by those who support federal recognition, saying they were a skewed sample of our people. But the fact of the matter is that Kānaka turned out in unprecedented numbers to express their manaʻo about our political present and futures. Our great leaders of the past, such as Queen Liliʻuokalani, showed us how important it is to truly listen to and consider the voices of the people. These testimonies are a huge resource and they should be taken seriously. If you are not moved by them, you are not listening closely enough.

The Context and The Testimonies

Remember that the DOI released its Advanced Notice of Proposed Rule Making, asking for public comment on its five threshold and nineteen additional questions in 2014 only eight days prior the first meeting in Honolulu, giving people little time to prepare. Remember that at each of the fifteen meetings on six islands, Kānaka voices resounded like pouring rain on corrugated metal rooftops. Remember that the vast majority of them asserted Hawaiian independence and refused US authority. Remember that the meetings were made accessible through grassroots efforts to livestream them. (Most of these meetings can still be viewed on YouTube.) Remember how many of us remained glued to our screens, watching person after person after person refuse cheap gifts of recognition. Remember how many Kānaka expressed deep distrust for the US. Remember how some said they wouldn’t answer the DOI’s questions until Secretary of State Kerry answered Kamanaʻopono’s. Remember how the DOI left and life went on. Remember also how, in 2015, when the DOI released its proposed rule, they essentially ignored those voices and only counted the written testimonies, most of which were identical postcards.

Several months ago, I printed out the transcripts from all of those public meetings. Over nine hundred pages, they completely filled a large box that took two people to lift. The transcripts would have been even longer if the contracted professional transcribers understood the Hawaiian language. Instead, most of the transcripts just say “[speaking Hawaiian]” when a speaker chose to use our mother tongue. This happened fourteen times in the Keaukaha meeting alone, leaving out valuable manaʻo from the official record and showing that the DOI did not deem our language valuable enough to find translators.

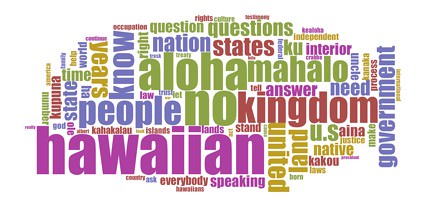

A visual representation of the most frequently used words at the DOI public meeting in Keaukaha, Hawaiʻi, July 2, 2014

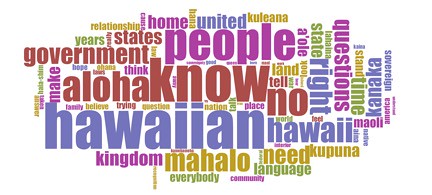

I ran each community’s transcripts through a text-mining program that analyzes, among other things, the frequency of words used. What stood out to me was how often the words “know” and “no” were used. After words like “Hawaiian,” “people,” and “aloha,” no and know were usually among the top five and always among the top ten most frequently-used words at every meeting on every island. So this got me thinking: What knowledge were people asserting? How were know-ing and no-ing linked, if at all?

A visual representation of the most frequently used words at the DOI public meeting in Lahaina, Maui, July 7, 2014

The time that I have spent reading these hundreds of pages of words of our Kānaka have shown me that there is a direct link between what people know and why they say “no” to the DOI and to federal recognition. The recurring phrase, “now we know,” comes directly from testimonies offered at these meetings and signals the impacts of massive educational efforts to uncover the history of Hawaiian independence over the past few decades. Our self-educational initiatives shifted the political grounds on which Kanaka stand. Forefronting broad-based popular education, Hawaiian social movements have greatly contributed to Kanaka Maoli assertions of cultural, genealogical and political identity. These “knowings” form the basis of a powerful refusal of settler state frameworks of recognition. Often speakers were asserting knowledge through “I know” or “we know” statements. Sometimes they were speaking about what is commonly known by the people and government of the US, but not acted upon. Other times they were telling the DOI panelists what they should know.

Here are eight overlapping categories of knowing—eight reasons—that fuel Kānaka refusal of US authority and of federal recognition. For each reason, I have selected a couple of salient examples from the testimonies to illustrate these themes, though there are hundreds more waiting for those who take the time to read them.

Ka Lāhui (collective identity)

One of the most common forms of knowing that Kānaka asserted was knowledge of “who we are” as Hawaiians, such as in this quote:

“We don’t need recognition. We know who we are in the hearts and minds of our people.”

(Remi Abellira, June 23, 2014 in Honolulu, Oʻahu)

These assertions of peoplehood were frequently expressed through connection to land and to an independent polity.

“We are Hawaiian subjects, as our kūpuna before us, who signed the Kūʻē Petitions of 1897. They laid a firm foundation for us. And all we have to do is remember and stand together with courage and let the United States, the State of Hawaiʻi, and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs know that we know who we are.”

(Leilani Lindsey Kaʻapuni, July 2, 2014 in Hilo, Hawaiʻi)

As this second quote illustrates, the affirmative statements were often paired with related statements in the negative (ex. “we are not Americans,” or “we are not an Indian tribe”) and/or with a rejection of recognition, based on the sentiment that because “we know who we are,” we don’t need an external entity such as the US to tell us.

Ka Moʻolelo (historical knowledge)

This theme represents the common rhetorical move that many testifiers made in calling upon facts of history.

“Congress can never create a congressional act to annex a country without a treaty. And they know it. Okay. They know it.”

(Kekane Pa, June 30, 2014 in Waimea, Kauai)

Such facts were sometime raised to dispel myths of history, such as the notion that the US legally annexed the Hawaiian Kingdom, exemplified by the quote above. Both Kekane Pa’s quote above and Josh Noga’s below also show the ways people emphasized that these facts are now well known but remain unacted upon by the US.

“There’s been a wrong, and you guys know the wrong. Everybody knows the wrong. They apologized in 1993, [with] the Apology Resolution. You violated the sovereignty of the Hawaiian Kingdom. But more importantly, you continue to deprive Kanaka Maoli of our human rights.”

(Joshua Ioane Noga, June 25, 2014 in Heʻeia, Oʻahu)

Assertions about historical knowledge were not just about the past but were marshaled to show how these histories ongoing relevance in the present and provide a basis for contemporary Kanaka resistance to US-determined political futures.

“We know the truth of our lahui’s history. It is this truth that compelled our kupuna to resist the United States’ occupation in these islands over a century ago, and it is this truth that has empowered many of us to continue on in this conscious struggle for the pono of our ʻāina and our lāhui today.”

(Noʻeau Peralto, July 2, 2014 in Hilo, Hawaiʻi)

Ka Moʻokūʻauhau (genealogical knowledge)

Ka Moʻokūʻauhau represents genealogical knowledge, which is more intimate than historical knowledge. Speakers referenced not only facts that they learned in schools or books, but spoke specifically about understandings that were directly transmitted within their families.

“I was seven years old when my tutu-man was with me, and all the ruckus was going about statehood, and as a seven-year-old, I said,

ʻPapa, what does that do for us?’

He said, ‘Nothing.’

I said, ‘Did you vote, Papa?’

‘No.’ He says, ‘They do not represent you.’ Know who you are. And I know who I am.”

(Sandra Phillips Pa, June 25, 2014 in Heʻeia, Oʻahu)

In many instances, testifiers spoke about elders who inspire their current political positions. Often these kinds of statements were about a familial connection to a legacy of kūʻē (opposition and resistance)

“I am here preserved by my ancestors that signed that Kūʻē Petition. My grandfather was 11 years old. My great-grandfather, the whole ʻohana was there in 1897 in that Kūʻē Petition. That made me a Hawaiian nationalist. I know who I am, and I am very proud … ‘aʻole to all the five questions for the record.”

(Renee Kanoi Bonnie Medeiros, June 30, 2014 in Waimea, Kauaʻi)

Ka Hoa Paio (opponents)

A corresponding counterpoint to Kanaka assertions of knowing “who we are,” the testimonies also include numerous examples of people making statements to the effect of: we know who you are as representatives of the US as well. The “you” in these comments was not typically aimed directly at the individuals sitting on the DOI panel, but rather the larger “you” of the United States and its role in oppressing Hawaiian people and nationhood.

“I don’t know you guys personally. But I will say that I no trust what is going on. Not because I do not trust you guys as individuals, but we can only trust the fruit that comes from the tree, you know. And the fruits from the tree so far will show bad fruits, was bad for us. And the taste in our mouth is bitter and we’re tired of it.”

(Hawaiʻiloa Mowat, June 28, 2014 in Kaunakakai, Molokaʻi)

Assertions of knowing the US were frequently tied to an expressed sense of distrust that grows out of the experiential knowledge of the US-Hawaiʻi relationship.

Ke Kuleana (authority)

The theme of kuleana overlaps with the previous themes, in terms of building on knowledge of collective self, history, and genealogy. But the statements within this theme went further to explicitly address who does and does not have authority or jurisdiction in Hawaiʻi.

“If you knew just a little bit about our nation’s history and your nation’s history and relationship with our nation, then you would see, like so many people have already been saying, that you have no jurisdiction here. And so I don’t really feel a need to answer your questions in the first place, but because I know how your nation does things, I will say no, no, no, no, no…you have to go back and talk to the people who have the power in your nation. Or better yet, you know, if you want to give up your citizenship and come and join us, I’m sure we can talk story about that.”

(Shavonn Matsuda, July 5, 2014 in Hana, Maui)

Both Shavonn Matsuda’s quote above and Kale Gumapac’s below illustrate that these discussions of jurisdiction were also connected, at times, to instructions about how the US government or specific individuals could enter Hawaiʻi in a more respectful way to actually demonstrate a genuine desire for a nation-to-nation, government-to-government relationships.

“The constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist. You need to learn that constitution so that you can know when to ask permission to come into the Kingdom of Hawai`i. You did not ask that permission and I don’t know who invited you in, but they did the wrong thing.”

(Kale Gumapac, July 2, 2014 in Hilo, Hawaiʻi)

Ka Hilinaʻi (self-confidence, trust, belief)

While related to the theme of Ka Lāhui (collective identity), statements within this theme explicitly expressed confidence in Hawaiian capacity to govern ourselves in the present.

“We are wiser, we are smarter, we know what to do and we’ll govern our nation.”

(Kaipuaʻala Crabbe, July 2, 2014 in Hilo, Hawaiʻi)

In the example from ʻIʻinimaikalani Kahakalau below, this self-confidence was directly tied to self-knowledge that comes from cultural practice.

“I’m a student at U.H. Hilo, I’m a Chancellor’s Scholar, I’m a cultural practitioner, and I am saying no to all five of your questions. And the simple reason is because we can do it ourselves, ’cause we know ourselves the best. We can answer anything we need.”

(ʻIʻinimaikalani Kahakalau, July 2, 2014 in Hilo, Hawaiʻi)

Thus, such rejections of US authority were centered more on a self-assuredness of Hawaiian capacity for self-governance. We are the ones who know best how to govern ourselves. And this assertion of self-confidence was often accompanied by a critique of US ineptitude or violence in its treatment of Hawaiʻi.

Ke Kūʻike (recognizing one another by sight)

Most testifiers came to speak directly to the DOI panel, but in a handful of instances speakers seemed to be moved by the experience of seeing so many of their fellow Kānaka coming forward and thus began speaking to each other.

“It is wonderful to know that one day when I put my kino in the ground, that I know that in the future, the faces of our young people that’s here tonight, I can rest in peace, that you’ve come tonight to bring your voices, that you will stand for the journey that our people have sat for you. Your life is in — and the life of our people and our nation is in your hands. We trust you, we beg you to rise to the moment now and forever.”

(Dawn Wasson, June 25, 2014 in Heʻeia, Oʻahu)

This theme of ke kūiʻke, then, represents the knowing that resulted in the very moment of seeing, with their own eyes, other Hawaiians present and expressing themselves. In other words, it is a theme regarding the knowledge of collective self-recognition that grows out of direct sight and the feelings that arise when we come together as a lāhui. In the instance below, the speaker spent most of his three minutes explaining to the panel how he has seen “over 46 years of decimation of our Kanaka lifestyle. Thanks to the capitalism and greed that comes along with Americana.” But as time ticked down and the facilitator prepared to cut him off, he turned to speak to his fellow Kānaka,

“You’re looking into my eyes and my heart. Okay. So I’ve got 30 seconds…We need to get together as Kanaka Maoli. We need to get together and become strong. We can do this. We don’t need anybody else. It’s a five no.”

(Abraham Kaiwaiwa Makanui, July 1, 2016 in Kapaʻa, Kauaʻi)

Ka Hoʻomau (continuing to future generations)

Testifiers at the 2014 DOI meetings were aware not only of the people who were physically present in the room. Many were also conscious of the ways in which their words might be preserved for future generations. Thus, expressions within this theme spoke directly to what speakers want for future generations to know

“I am here to answer the five questions that are posed, and my answer to all five questions is no. I am opposed to the proposed rule change, I am opposed to federal recognition. I am opposed to the illegal U.S. occupation of Hawaiʻi. I wanted to come here tonight so that my opposition would be added to the historical record of these meetings, so that my keiki and my descendants will always be clear about how I felt about this process and your government, which was very much in line with the majority, the vast majority of testimony you’ve heard over the past week and a half. So they can look back, in much the same way you look back to the Kūʻē Petitions of our kūpuna who opposed annexation of Hawaiʻi to the United States.”

(Kuʻulani Muise, July 2, 2014 in Hilo, Hawaiʻi)

In Kuʻulani Muise’s and Alona Naomi Quartero’s quotes, above and below, both women connected past and future generations, situating themselves within a continuum of resistance.

“I will definitely let my children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren know that an injustice was done. So I stand here for them, knowing that I know that my tūtū signed the petition against annexation. I know our Queen did not want this. So I stand here, knowing all of this, to let my grandchildren know that I am here today.”

(Alona Naomi Quartero, July 2, 2014 in Hilo, Hawaiʻi)

These eight forms of knowing sustained Hawaiian refusal of the limited forms of recognition or, more precisely, what Glen Coulthard has rightly pointed out are settler state misrecognitions, at the 2014 DOI consultation sessions on its proposed rule for establishing a federal recognition process for Native Hawaiians.

A Few Closing Thoughts

If the DOI invested the time and energy to have face-to-face public meetings in fifteen Hawaiian communities on six islands, why did they ignore the overwhelming majority of the oral testimonies as they developed the final rule? For instance, in the final rule that was released a few days ago, these voices are quickly dismissed:

“Many commenters objected to any rulemaking by the Department, indicating their belief that Hawaii was illegally annexed by the United States, that Hawaii is currently being ʻoccupied’ by the United States, and that the Kingdom of Hawaii continues to exist as a sovereign nation-state independent of the United States… Response: The Department made no changes to the rule in response to these comments, which address the validity of the relationship between the United States and the State of Hawaii. To the extent commenters claim that Hawaii is not a State within United States, the Department rejects that claim. Congress admitted Hawaii to the Union as the 50th State. (p.60)

Perhaps DeMont Connor’s testimony provides a response to the question of why the US government would essentially ignore the overwhelming majority of testimonies at the only public hearings on federal recognition to ever be held on multiple islands throughout Hawaiʻi.

“This thing that you guys doing right now, it’s like I went steal your car, but I come to you and I tell you I no can give you back your car, but I gonna give you this brand-new bicycle, yeah, from Schwinn, the best top of the line, and I still jump in your car and I drive away. Come on, brah, we don’t need this. I apologize for you guys come all the way over here for this. I want to say Esther Kiaʻaina, aloha to you, sister. You know, we recognize you. Unfortunately you stay over there with them over there. Come home, sister, come home.”

(DeMont Conner, June 23, 2014 in Honolulu, O‘ahu)

The thief does not want to return the stolen goods. The DOI final rule illustrates this clearly when it “further clarifies that reestablishment of the formal government-to-government relationship does not affect the title, jurisdiction, or status of Federal lands and property in Hawaii” (p. 50). The language throughout the rule is also clear in asserting US plenary (meaning supreme) power over Indian affairs, under which it considers Native Hawaiians. Kānaka who oppose the rule are not attempting to foreclose options for our people. We refuse to assent to the US assertion of supreme authority over our lāhui and ʻāina.

Especially when we know that the US government uses recognition frameworks as a way to legitimize its seizure of Native lands, and when we know it has no intention of handing title of the lands it currently controls over to Hawaiians, we Kānaka really need to come together and have some hard conversations. For me, the 2014 oral testimonies to the DOI are evidence that the multi-generational work of nation-building makes the most lasting gains when Hawaiian people have taken a bottom-up approach to nation-building, focusing on broad-based education rather than on external recognition. The sentiments of distrust and refusal evident in the testimonies reject not only US federal and state recognition, but also top-down, non-inclusive, non-transparent, elitist politics that have not been patient in or committed to building broad-based conversation and consensus. Let’s change that together and recommit to meeting each other face-to-face and taking as long as we need to work this shit out together.

Kumu, not sure if my first reply registered, I was in flight when I tried sending, e kala Mai…

Your essay/op-ed is powerful, very eloquently communicated, carefully researched in factual account and crucial in timing and focus. I think it should be communicated statewide via every means acceptable and available (besides social media and this wordpress site).

Mahalo nui loa for your continuing efforts to bring justice to bear in this long-standing controversy, steeped in US imperialistic policy and refusal to admit to and rectify injustices that span its 250-year history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

E no’o no i ka olelo-maupopo?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy greetings,

thank you for being here, and thank you for sharing.

Ron

LikeLike

Mahalo to all Na Kanaka’s for standing up to the bullies of the world the united states … It doesn’t seem to make any sense that the out come from DOI is federal recognition even against our will of self governance….. the truth will always rise above and come to light… we the Kanaka forever protest against the annexation of the Hawaiian Kingdom… a joint resolution can cross international waters and we total understand that the DOI and the united states has no jurisdiction in Hawai’i… let our people go!!!! Take your rules and laws and leave… mahalo

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mahalo for sharing this in depth dissertation with us. We are seeing an awakening of human consciousness globally and within the islands. A shifting of polarities is underway physically and spiritually. Wrongs will be righted and justice will prevail.

LikeLike

John 10:10

The theif cometh not, but to steal, kill and destroy

STOLEN LAND’S

GENOCIDE A RACE

SEGREGATE THEIR MIND’S

YOU WILL NEVER DESTROY THE SPIRIT OF NA KANAKA!

NO IS NO! IN ENGLISH THE WORD NO MEAN’S, WILL NOT CAN NOT, DO NOT WANT, NO LIKE!

NO! DOI

NO! FEDERAL RECOGNITION

NO! UNITED STATE’S GOVERNMENT

LikeLike